Pop culture’s ongoing sapphic explosion

Written by Ashley Schofield

Happy Pride Month!

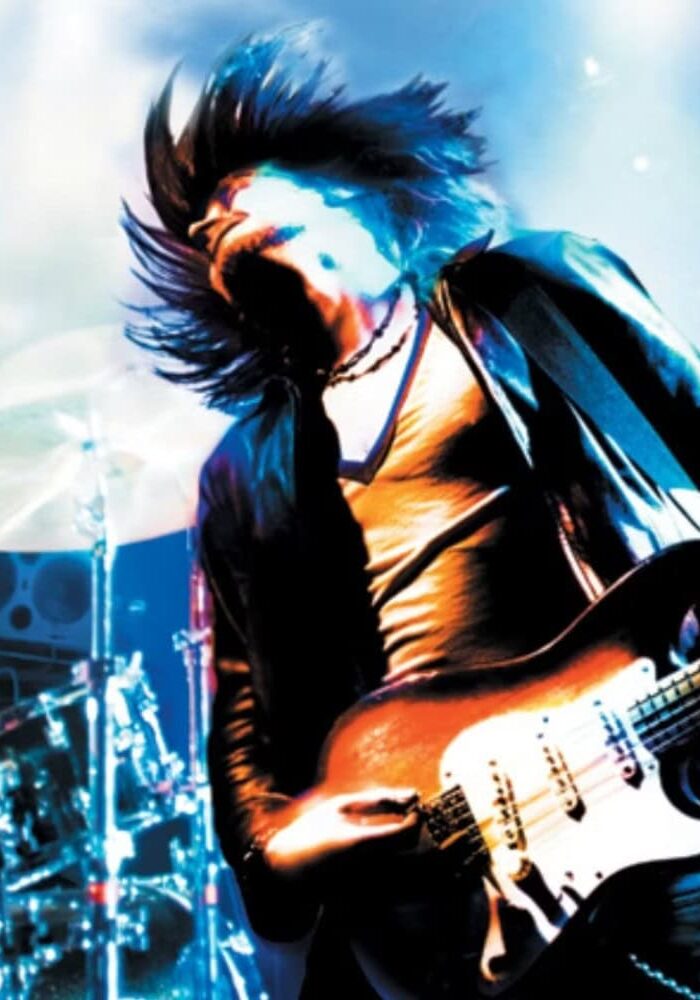

It’s a damn good time for sapphic representation. To put it one way, lesbians are eating good right now. For the first time in a long time, art made for and by the sapphic community is comfortably back in the mainstream, not hidden away just in queer spaces we have to actively look out for. In a society that is questionably accepting of queer people and laden with widespread governmental legislation created to crush their true selves, it is wonderfully anti-establishment and counterculture for artists and fans to be proudly and unapologetically queer. A shining example of this phenomenon is in the contemporary music industry, thanks to massive sapphic icons like Chappell Roan (pictured above) as well as many others. These artists are all linked in writing and singing openly and proudly about their intense and powerful love for women as partners and as people, yet each approach the queer zeitgeist from very different angles.

Roan’s 2023 debut album, The Rise and Fall of a Midwest Princess, explores an incredibly wide spectrum of the lesbian experience, offering a complex view into her closeted upbringing as a lesbian in Missouri, her poor experiences with comphet relationships started due to a fear of being her true self, and finally her rebirth as an openly queer icon in Los Angeles. The album’s opener, Femininomenon, directly addresses Roan’s feelings towards dating men, citing the reality of a woman giving so much – ‘pictures and playlists and phone sex’ and a man giving nothing back, just disappearing as soon as Roan asks for something concrete with him. Similarly, the Tiktok-famous Casual addresses the pitfalls of the all-too-common situationship, lamenting her depression at the idea of being ‘just a girl that you bang on your couch’, suffering in a no-strings-attached fling in which she absolutely would prefer for there to be tight strings between them.

Roan’s in-album character development hits its next stage in Super Graphic Ultra Modern Girl, complaining that her male date ‘wouldn’t dance / he didn’t ask a single question’, before confidently exclaiming that she’s done with these ‘hyper mega bummer boys’ and is looking towards what she’s been denying herself all this time: the eponymous ‘super graphic ultra modern girl like me!’ And finally, under the lights of a Santa Monica drag club, Roan welcomes in her rebirth as a star of the Pink Pony Club. This song not only celebrates the self-love of being openly queer, ‘just having fun / On the stage in my heels […] where I belong’, but also makes it clear that Roan has moved past the fear of disapproval and homophobia that kept her in the closet for so long. Existing as an allegory for both the sapphic and trans experience, Pink Pony Club is Roan’s joyous eulogy of her old self. She knows she won’t make her mother proud, who’ll scream ‘God, what have you done?’, and doesn’t let it keep her down – those days are behind her.

As a sort of digestif to the messages of her album, the later-released single Good Luck Babe serves as bittersweet advice to other queer women to not repeat her painful comphet experience and be themselves. The hook, ‘You can kiss a hundred boys in bars / Shoot another shot, try to stop the feeling’ is a microcosm of being comphet: doing anything they can to push down their feelings towards women, accepting the worst of men just to ‘stop the feeling’ and shield themselves from prospective homophobia. Yet Roan minces no words in the bridge, warning women of the heterosexual standard of women becoming ‘nothing more than his wife’, bitterly stating ‘I told you so’, wishing it hadn’t turned out this way for them. The raison d’être of Roan’s discography is to encourage lesbians to be themselves, regardless, as it’s always better to be true to your queerness than repress it due to societal homophobia.

Chappell Roan is, of course, far from the only sapphic artist in the contemporary zeitgeist. Looking slightly to the past, the queen of lesbian indie pop girl in red (Marie Ringheim), has become so synonymous with contemporary sapphic culture that “Do you listen to girl in red?” has become a subtle sapphic check – a musical equivalent to spotting a carabiner hanging off a belt loop. Ringheim’s i wanna be your girlfriend is a touch more restrained than Roan’s lyricism but still not subtle in its intention, with the chorus repeating the yearning ‘I don’t wanna be your friend, I wanna kiss your lips’ until later transforming the line into the more direct ‘I don’t wanna be your friend, I wanna be your bitch’. Yet it is precisely this quality that made its existence so groundbreaking – a ballad of sapphic yearning released quietly on Bandcamp in 2018 that, over time, metamorphosised into an internationally beloved queer anthem. The success of Ringheim’s lyricism is no coincidence – the feeling of being lost in self-discovery and female yearning amidst comphet expectations is something universal to sapphic culture.

Similarly, the music of Clairo (Claire Cottrill]) occupies a slightly more optimistic postmodern take on sapphic reality. Cottrill’s 2019 single Bags feels like a slightly brighter interpretation of i wanna be your girlfriend’s themes – it also approaches the terrifying concept of falling for a friend, yet Cottrill somehow manages to distil this overwhelming feeling into just one warm line – ‘Can you see me? I’m waiting for the right time / I can’t read you, but if you want, the pleasure’s all mine’. Her most recent single, Sexy to Someone, evolves this yearning from quietly pining to a longing for intimacy, referring to the eponymous sexiness as ‘a reason to get out of the house […] just a little thing I can’t live without’. While the yearning for the soft love of a friend has not disappeared, the feeling is complicated by an unavoidable need for something more explicit, reflecting on the inevitable reality of sexual needs in sapphic relationships with the lyric ‘Is it too much to ask?’

While Roan, Ringheim and Cottrill are known as queer artists first, pop artists second, several well-known pop artists are also embracing more openly sapphic themes in their work. Reneé Rapp is no stranger to sapphic themes, with her 2023 single Pretty Girls lamenting the fetishisation and dehumanisation of lesbians by straight women as just a toy to be played with and discarded after trying something new. This track bears a uniquely bitter tone, with Rapp denoting her sexuality as ‘a blessing and a curse’ – a blessing in being open in who she is, but a curse in how that honesty makes her a forbidden fruit of sorts to people unwilling to treat her as more than a prop.

And while Billie Eilish’s latest album Hit Me Hard and Soft is certainly gay all over, it climaxes in the unapologetically sexual LUNCH – with lines like ‘You need a seat? I’ll volunteer’ and ‘I’m pullin’ up a chair / And I’m puttin’ up my hair’ being enough to make anyone blush – there is no room for subtlety or implication here. The existence of LUNCH, similar to Roan’s discography, is a microcosm of the evolution of sapphic content in recent years – while lyricism like that of Ringheim, Cottrill and Rapp solemnly reflects on the struggles of being a lesbian in a comphet, implicitly and explicitly homophobic society, Roan and Eilish loudly and proudly yell ‘fuck that, I’m gay as hell and you’re gonna like it.’

It’s not just in chart-topping tracks that sapphic themes are found, however – the games industry is also experiencing a lesbian revolution as of recent years. 2020’s sleeper music-based indie title Sayonara Wild Hearts shines with an all-female cast across its bubblegum pop soundtrack and blatantly bisexual lighting-inspired colour scheme, but the real sapphic gem is found in its story. Sayonara Wild Hearts is, at its core, a game about a heartbroken queer woman healing, moving on and accepting herself – it even ends with the protagonist kissing several of her female enemies to make peace with them and move forward, welcoming them back into her own heart.

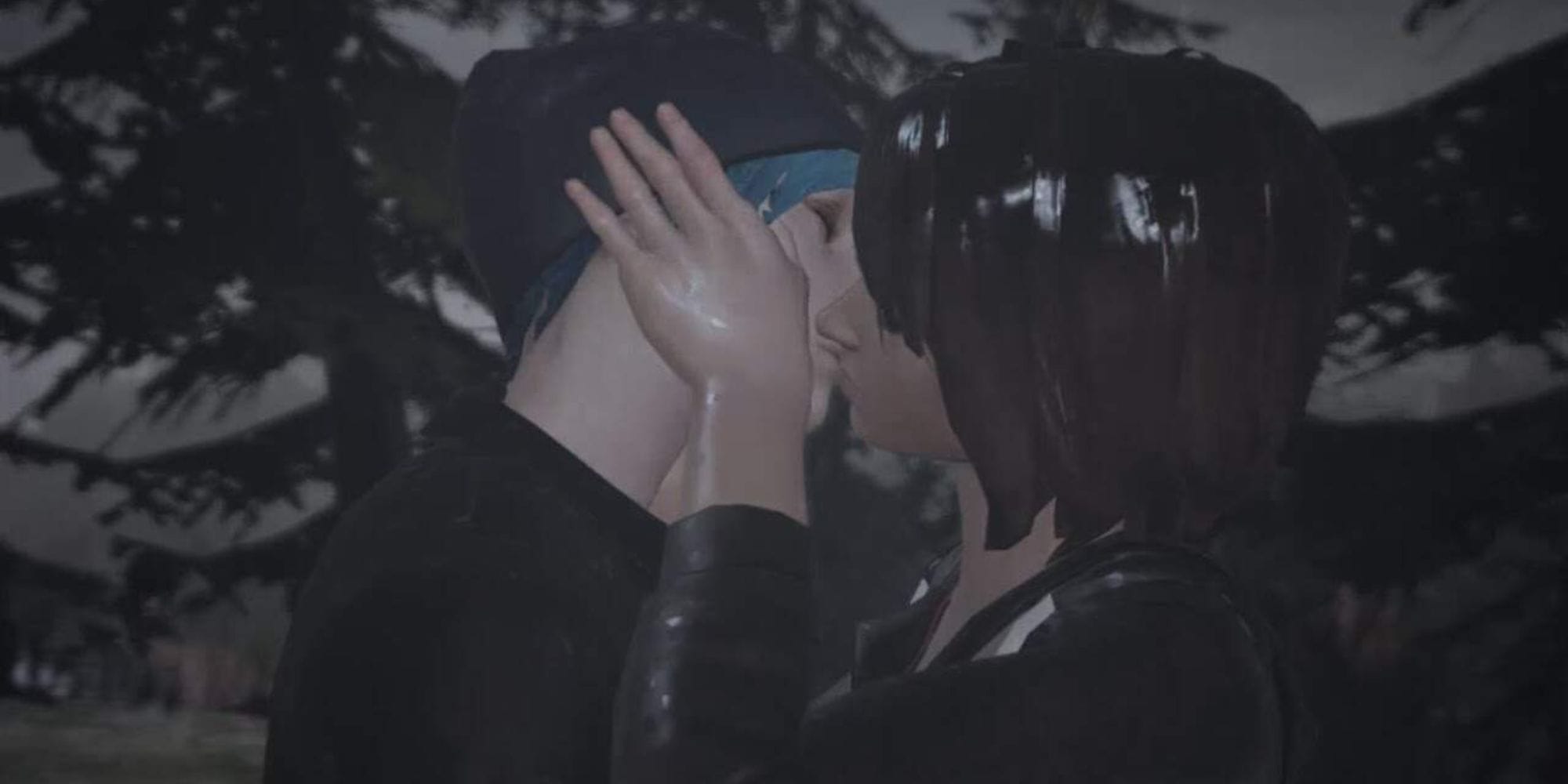

On the note of queer-coded games, Life is Strange is sometimes colloquially regarded as ‘the lesbian game’, and for good reason. Amidst its fantastical story of protagonist Max struggling with her ability to manipulate time, there lies a narrative of Max struggling even more to figure out just who she is. Joining Max in this journey is Chloe, her best friend and prospective girlfriend, who was no doubt a sapphic awakening for many self-questioning women – Max herself included. In a game built around individual choices, the final choice of the story presents Max with a blue-haired trolley problem: save Chloe’s life at the cost of thousands perishing in the oncoming storm, or sacrifice Chloe and let Arcadia Bay live on. While the latter appears to be the simply morally correct option, some people still chose to save Chloe; the complex writing of Chloe makes her lovable despite her flaws and self-destructive tendencies, so much so that she could be placed over an entire town so as not to lose the woman Max cares for most. Yet even preceding her death, some of Chloe’s final words are “I’ll always love you”, followed by her and Max finally sharing the kiss that the entire narrative has been leading up to. Life is Strange presents the player with the complicated reality of being queer: there will always be uncertainty, pain and tragedy, but there will always, always be love.

It’s possible that you’ve been yelling “BALDUR’S GATE 3!” at the screen since games were brought up, and you wouldn’t be wrong. Shadowheart, Karlach, Lae’zel and Minthara have become sapphic icons in themselves, occupying several different genres of lesbian attraction, with the first three becoming the top three most romanced companions regardless of player gender. While companions in Baldur’s Gate 3 are written to be ‘playersexual’ rather than explicitly straight or gay in ignorance of the player, these three are most certainly sapphic-coded at the very least. Lines such as Karlach’s offering of “tracing every curve of your body with my fingertips” or “kiss you for as long as you’d let me” is the kind of feminine intimacy that you’d read in a sapphic Hinge chat a few dates in, far from standard hetero RPG romancing dialogue – let alone the actual queer sex scenes, which are simultaneously something to behold and also incredibly considerately thought-out to be accurate to queer intimacy. With Baldur’s Gate 3’s romances being written with the idea of queer flexibility in mind first, rather than an afterthought following heterosexual normalcy, there is a wonderfully unavoidable queer nature to its romances that has proven key to making it so popular within the community.

In all of this queer art, in all their varied methods to present the sapphic experience, one core message binds them all: queer people are not alone, despite the world seemingly being against them at every turn, and even a world as often bigoted as our own doesn’t have the power to snuff out the light of their self-love.

Enjoyed this story? Support independent gaming and online news by purchasing the latest issue of G.URL. Unlock exclusive content, interviews, and features that celebrate feminine creatives. Get your copy of the physical or digital magazine today!

Little Kitty Big City: The Warmth of Cosy Gaming

Proof That Sometimes the Purr-suit of Happiness Is as Simple as Being a Cat Written by Rose Renaud The mainstream popularity of the casual games genre has exploded in recent years. They have always been around and possess a sense of nostalgia with series like Animal Crossing and The Sims. They were worlds where we…

Strange Horticulture: Unraveling Mysteries One Leaf at a Time

In this botanical whodunit, the only thing sharper than your shears is your wit. Written by Janelle Hyde Strange Horticulture is an immersive game that excellently captures a somber tone. Set in the fictional town of Undermere, players inherit a plant store and navigate a world filled with botanical mysteries and magical properties. The game…

Petra Collins’ “I’m Sorry” Collection

A Whimsical Wail of Nostalgia and Glamour Welcome back to the dreamy, cotton-candy universe of Petra Collins, where the boundary between reality and fantasy is as blurry as your latest Instagram filter. With her reimagined collection, “I’m Sorry,” Petra is serving us a triple scoop of nostalgia, art, and high-fashion collaboration. Let’s dive into this…

Sonny Angels: The Cherubic Collectibles You Didn’t Know You Needed

Sonny Angels don’t just give you wings – they also lighten your wallet! Alright, let’s dive into the world of Sonny Angels. Picture this: you’re wandering through a labyrinthine Japanese department store, and suddenly, you’re ambushed by a horde of tiny cherubic figures. Each one is donning an outrageous headgear – a strawberry, a panda,…

5 Must-Watch Runs From SGDQ 2024

Dive Into the Best of Summer Games Done Quick with These Five Unmissable Speedruns Written by Terry Ross Once a year, thousands of gamers turn off the cosy droning of the YouTube lo-fi beats streams which accompany their workweek and switch over to something far more exciting: the summer Games Done Quick speedrunning marathon. For…

Rock Band: The Game That Defined Your Music Taste Without You Realising It

The Unsung Influence of Rock Band and Guitar Hero on Modern Emo and Music Culture Written by Kayla Moreno Y2K and its subcultures have been seeing a massive resurgence over the past several years. It’s known that when people crave a sense of comfort, nostalgia waves often bring them peace. Things that are reminiscent of…

Gaming Purity and the Attitude Towards Cheats and Wikis

The Holier-Than-Thou Attitude Towards Cheats and Wikis in Single-Player Games In the hallowed halls of single-player video games, there’s an unspoken hierarchy among players—a purity test, if you will. On one side, you have the self-proclaimed purists, those who wear their struggle and perseverance like badges of honor. On the other, there are the pragmatists,…

Katy Perry Returns with “Woman’s World”

A Controversial Comeback for the Singer’s Sixth Studio Album Katy Perry has once again graced the pop music scene with her latest single, “Woman’s World,” released today, July 12, 2024. This track marks a significant moment in her career as it’s the first single from her upcoming, yet-to-be-titled sixth studio album. Perry’s announcement and teasers…

Defining The Fashion Metaverse

Redefining the Digital Luxury Experience The concept of the fashion metaverse has rapidly evolved from a niche experiment to a burgeoning frontier where technology, fashion, and social interaction converge. With platforms like DREST leading the charge, the metaverse offers a transformative space for brands and consumers alike. This thought piece explores the intricate dynamics of…

Is the IT Girl Just an Online Girl?

Reflecting on the broader implications of digital culture on today’s celebrities In the kaleidoscopic realm of contemporary culture, the concept of the “It Girl” morphs and mutates, perpetually reinventing itself to mirror societal shifts. Once defined by fleeting glimmers in the tabloid spotlight, today’s It Girl is enmeshed in the digital ether, her identity coalescing…